Yayoi Kusama’s Infinite Influence

Many of the most revered artists of the past century were profoundly impacted by their time in and around our neighborhoods. Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama has risen above even those icons to become the top-selling female artist on the planet, all while developing a style that is as immersive as it is iconic.

Born March 22, 1929 in Matsumoto City, Nagano prefecture, Japan, Kusama grew up on her family’s plant nursery and seed farm. She began experiencing hallucinations when she was ten years old, flashes of light, auras, or dense fields of dots. She began drawing around the same time, including sketches of pumpkins which would later become a signature of her work. Kusama’s mother forbade the young artist from painting or creating artwork of any kind, insisting that her daughter was destined to marry a rich man and become a housewife.

Nevertheless, Kusama went on to study traditional Japanese Nihonga style at Kyoto Municipal School of Arts and Crafts after high school graduation in 1948. She soon grew frustrated with the style, however, and began creating work in the style of European and American avant-garde. After success in the Matsumoto and Tokyo galleries, she moved to the United States in 1957. She spent a year in Seattle working on an exhibition. Yet, she found that New York was calling to her.

Kusama moved to 70 East 12th Street in 1958 following encouraging correspondence from fellow artist Georgia O’Keeffe. She found life in New York to be artistically enriching, but much more trying than her year in Seattle. As a Japanese woman living in a major city after WWII, Kusama faced much more hardship than many of her white, male peers. She often painted at night without heat and ate from restaurant dumpsters. Despite these trials, Kusama soon found acclaim. She debuted at Brata, a gallery at 89 East 10th Street run by and for artists, in 1959 to the delight of critics, artists, and collectors alike. It was there she debuted her Infinity Nets which were lauded for their hypnotic allure.

Kusama soon became a central figure in the downtown New York avant garde arts scene. She frequently staged exhibitions, including at the ‘1961 Whitney Annual’ at the Whitney Museum of American Art. However, Kusama was regularly hospitalized due to overwork, spurring a concerned Georgia O’Keeffe to convince her own dealer to purchase works to help Kusama stave off financial hardship.

Her immersive work exploded in 1965 when she opened her first Infinity Mirror Room – Phalli’s Field. Kusama affixed thousands of fabric spotted tubers to the floor and furniture, echoing her previous Accumulations sculptures. She then covered the room’s four walls in mirrors, creating an infinite reflection so that one felt they were standing in an endless field of spotted tubers. This whimsical, surreal, and immersive installation became a signature style for Kusama, whose own visions seemed to be brought to life to be shared by her audiences.

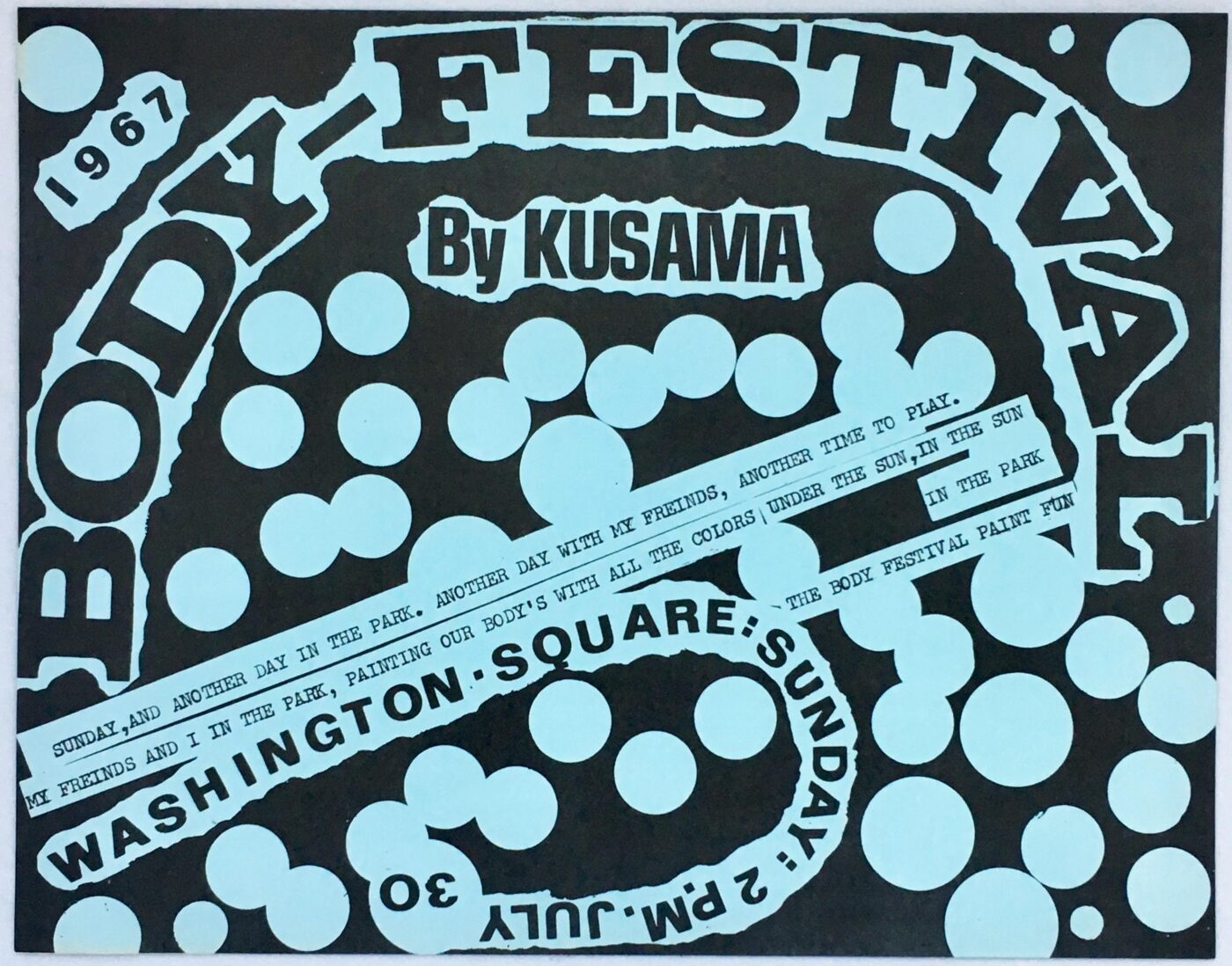

Kusama also made headlines for her public nudist gatherings in the late 1960s, reveling in the counterculture and anti-war sentiment that was sweeping the nation. In 1967 she invited New Yorkers to her “Body Festival” in Washington Square Park where they would strip. Kusama would cover them in her signature painted polka dots, and all would “play” in the sun. The “High Priestess of Polka Dots” also presided over a 1968 gay wedding at the Church of Self-obliteration at 33 Walker Street. That same year she performed alongside Fleetwood Mac and at the Fillmore East.

Despite these successes, Kusama continued to be plagued by ill health and increasing paranoia. She believed her male peers, including Andy Warhol, Claes Oldenberg, and Lucas Samara were stealing her work while receiving far greater attention for it. She took to covering the windows of her gallery to prevent outsiders from looking in. This deterioration, combined with the rejection of her work by her family and Japanese community, led Kusama to attempt suicide.

Kusama returned to Japan in 1973 following her recovery. The country received her with little sympathy, however, viewing her bold work as distasteful and shameful. She became so depressed she was unable to work and made another suicide attempt. Thankfully, in 1977 Kusama encountered a doctor who used art therapy to treat mental illness in a hospital setting. She checked herself in and eventually took up permanent residence in the hospital by choice. Her studio, where she has continued to produce work since the mid-1970s, is a short distance from the hospital in Tokyo.

These tumultuous developments forced Kusama to build her career back from the ground up. After a quiet period of recovery and reflection from the late 1970s, Kusama once again rose to stardom with her work at the Japanese pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 1993. She crafted a dazzling mirrored room filled with small pumpkin sculptures in which she resided in color-coordinated magician’s attire, leading viewers through a shocking fantasy of color and brightness.

Since then, Kusama’s career has exploded like never before. Her stylized pumpkins have become a Kusama signature in the decades since, sprouting up to decorate landscapes around the world. Now her works are instantly recognizable, cementing her as one of the most successful and iconic artists of her time.